As Texas’ SB8 went into effect on September 1, 2021, Hurricane Ida continued to tear through the country, impacting both the Gulf region and the Northeast, and Western states and communities remained on high alert as they face record-setting wildfires. This temporal overlap must serve as a powerful reminder that barriers to well-being are intersectional – and they are intensifying. The need for access to comprehensive healthcare, crucially including reproductive care, grows exponentially when the disparate impact of natural disasters and environmental crises is considered. This need is the heart of calls for reproductive justice.

Loretta Ross, co-founder of SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective, articulated the goals of the reproductive justice framework in an interview with Ms. magazine:

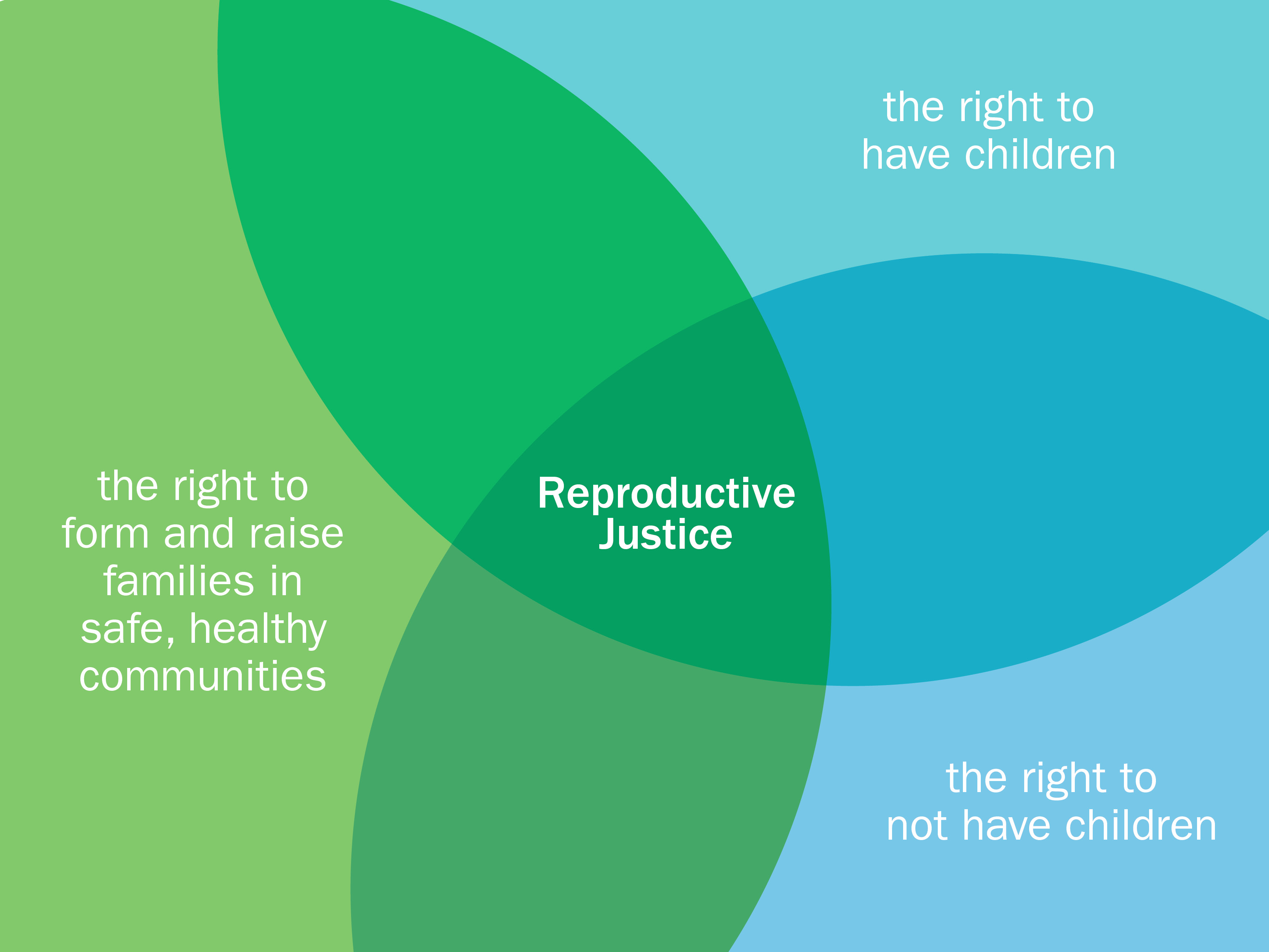

My biggest vision for reproductive justice is that it becomes a pathway for the full achievement of everyone’s human rights: the right to decide if and when you’ll have a child; the right to decide the conditions under which you birth your children; the right for your children to grow up in safe and healthy environments. I wish these things for all of humanity—regardless of where you live, who you are, or the gender with which you identify. Every human being deserves the same human rights.

Leaders of the Black Women’s Health Imperative link reproductive rights "with the social, political and economic inequalities that affect a woman’s ability to access reproductive health care services.” When birth activists advocate for safer conditions for women of color giving birth – especially African American women – they are working to bring about reproductive justice. When pro-choice activists assert that anti-choice activists only care about the fetus and not the baby after it's born, they are drawing on the reproductive justice ethic.

A dozen states other than Texas have passed laws in recent years to ban abortion after six weeks into pregnancy (just two weeks after a missed period, when knowing you might be pregnant depends, of course, on having a rigidly regular menstrual cycle). Those laws have been blocked in court for conflicting with the precedent established in Roe v. Wade decades ago. They also betray a woeful lack of knowledge about biology:

The governor’s answer demonstrates a common misconception about the law: Six weeks of pregnancy does not mean six weeks to get an abortion. SB 8 has been deemed the most restrictive active law in the country, largely because the window to get an abortion is limited to two weeks at most. Gestational age begins at the end of a previous period, and the first sign of pregnancy is often missing one’s period. A typical menstrual cycle lasts 28 days, or about four weeks. A person cannot get pregnant until after they have ovulated, which generally happens halfway through the cycle. That means that if someone has a perfectly regular menstrual period, they may know they are pregnant by what we call four weeks of pregnancy.

In my own motherhood studies scholarship, I have dedicated previous paragraphs and pages to the deep-rooted cultural as well as personal assumptions about motherhood that are revealed in the moment(s) when a woman is deciding whether or not to carry a pregnancy to term, navigating moral nuances, and choosing the least worst option available to her.

A law that isolates poor women from their entire support system does not support the well-being of the children they already have.

The Texas Tribune's coverage of SB8 notes that its novel enforcement mechanism is “a huge, unprecedented expansion of who can bring a lawsuit against someone else: Under the law, anyone can sue anyone who performs, aids or intends to aid in an abortion — regardless of whether they have a personal stake in the abortion performed.” The article also addresses the vagueness of what behavior is outlawed by the enforcement mechanism, which has legal experts worried about “an avalanche of lawsuits that could be launched against abortion providers, doctors, nonprofits, volunteers or even private citizens who help a family member or friend in getting an abortion.” SB8 specifically calls out anyone who “knowingly engages in conduct that aids or abets the performance or inducement of an abortion, including paying for or reimbursing the costs of an abortion through insurance or otherwise, if the abortion is performed or induced in violation of this subchapter, regardless of whether the person knew or should have known that the abortion would be performed or induced in violation of this subchapter." (Sec. 171.208.a.2)

There is a particular harm caused by this sweeping liability that I want to highlight:. Everyone in a woman’s support network is at risk of being held financially responsible for “aiding and abetting” an abortion for any support they provide, even the support of listening to them while they contemplate their options. The woman is effectively isolated in one of her (potentially) most vulnerable moments – which, ironically, makes it even more challenging for under-resourced women to carry their pregnancy to term. When we discuss abortion laws, it is imperative to consider who seeks and obtains abortions: poor mothers. Approximately 75% of those seeking abortions are poor or low-income, and 59% have already had at least one live birth. Rachel Jones’ research highlights this fact: “many if not most American women receiving abortions do so for reasons related to the wellbeing — often financial — of the children they already have.” A law that isolates them from their entire support system does not support the family’s well-being.

Key features of the cultural landscape within which SB8 is now taking effect are listed by David Perry and Sara McDougall in their recent Slate article. They point out that, “The Texas law that these ready and willing vigilantes are so eager to take advantage of coexists not with a general ethic of protection for women and children, but with child abuse and sexual exploitation of minors, high maternal and infant mortality rates in the Black population, lack of protections for pregnant women in the workplace, and the dangerous treatment of incarcerated pregnant women.” In this climate, the law “empowers and legitimizes harassment and uses the tested tools of slavery to carry out its antiabortion agenda.”

Reproductive justice advocates like Loretta Ross remind us how government withholding of reproductive rights works in the inverse. The same government empowered to enact laws like SB8 also implements laws and policies and encourages attitudes that interfere with many women (especially women of color) raising children to healthy adulthood – or even having children. To tweak a question Ellen Goodman posed years ago in a column on abortion, When will we understand this reality: a government that can force a woman to continue a pregnancy is the same government that can force a woman to have an abortion?

The EPA recently released a report detailing how worsening impacts of climate change will disproportionately impact minority communities in a “a federal acknowledgment of the broad and disproportionate effect that global warming is having on some of America’s most socially vulnerable groups.” Particularly vulnerable are pregnant people and newborns whose safety and well-being during natural disasters “have been a growing concern for health-care providers as more places in the country experience these kinds of traumatic events.”

The global pandemic has brought a margin of additional attention to existing inequities. Constraints on reproductive rights and climate change will both make those inequities increasingly pronounced. Working for reproductive justice keeps the interrelated nature of our most pressing challenges in focus and can inform better research, community engagement, and advocacy for the most vulnerable.