In July of 2017, we were in the early stages of planning the event that the Women’s Center would host for the 2018 Community MLK Celebration. I knew that I wanted to bring Loretta Ross to UVA for a public lecture, and she and I were in conversation about the theme and goals for her talk. After August 11th and 12th, we pivoted directions. When she came that following January, she delivered a powerful talk on her concept of "calling in". It was a message our audience deeply appreciated.

But I still regret that we didn't get to hear the lecture we had originally planned on her giving: a discussion of reproductive justice.

Ross is a co-founder of SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective. In an interview with Ms. magazine, she articulated the goals of the reproductive justice framework:

My biggest vision for reproductive justice is that it becomes a pathway for the full achievement of everyone’s human rights: the right to decide if and when you’ll have a child; the right to decide the conditions under which you birth your children; the right for your children to grow up in safe and healthy environments. I wish these things for all of humanity—regardless of where you live, who you are, or the gender with which you identify. Every human being deserves the same human rights.

Osub Ahmed and Christy M. Gamble explain the work of the Black Women’s Health Imperative: “Reproductive justice links reproductive rights with the social, political and economic inequalities that affect a woman’s ability to access reproductive health care services.”

When birth activists advocate for safer conditions for women of color giving birth – especially African American women – they are working to bring about reproductive justice. When pro-choice activists assert that anti-choice activists only care about the fetus and not the baby after it's born, they are drawing on the reproductive justice ethic. A recent NPR/Marist/PBS News poll confirms my read of this particularly fraught cultural conversation that has gained new salience and fervor in the past few years with increasing efforts to legislate access to abortion. The survey recorded “a great deal of complexity — and sometimes contradiction among Americans — that goes well beyond the talking points of the loudest voices in the debate.”

In the moment(s) when a woman is deciding whether or not to carry a pregnancy to term, deep-rooted cultural and personal assumptions about motherhood are revealed.

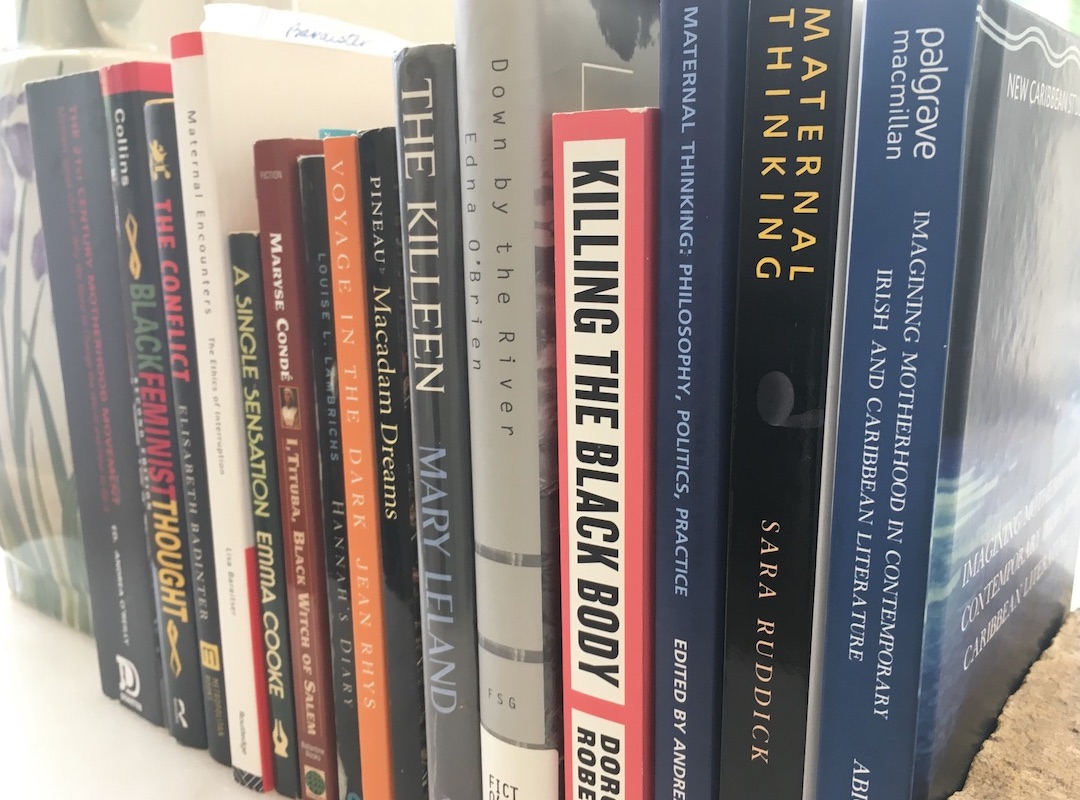

During my doctoral studies, when I began contemplating a dissertation topic, I early and easily identified motherhood as my broad area of scholarly interest. Looking back through all of the papers I'd written for my courses, very few didn't in some way at least touch on maternal concerns. It took a while and some false starts to narrow that topic to a manageable scope. One of the most formative moments came in a course on feminist theory and the Catholic intellectual tradition that I took late in my graduate studies. I was a fourth-year, dissertating student, and a visiting scholar, Cristina Traina, was offering this course.

That fall, I was grappling with a chapter that was looking at novels published in the 1990s. One of the common threads connecting Irish and Caribbean women’s writing in the 1990s was their near-universal concern with the pressures mothers face in late twentieth-century postcolonial societies. In particular, I was struck by how ubiquitous abortion was as a narrative element running through this body of novels. Read enough 1990s novels, and you develop a schema: mother-daughter relation, check; girls’ access to education, check; family trauma, check; women’s developing sexuality, check; pregnancy and abortion, check. Abortion, it quickly became clear, was a plot element to be expected in Irish and Caribbean women’s writing, and this new ubiquity intrigued me.

Cristie pointed me in the direction of some feminist theologians to help me think through these narrative moves:

Patricia Beattie Jung reminds us that “Pregnancies become problematic when no way of balancing the various responsibilities [the woman’s physical and emotional health and life-situation, the value of and likely impact of pregnancy upon her life-plan, the extent to which the community will support her and her dependents, the value of the child’s life as well as the child’s best interests, and any special responsibilities of a contractual origin that the woman may have to either the child or others] can be found”.

Beverly Wildung Harrison advances a vision of the day that “the decision to bear a child, for all women, is a moral choice – that is, a deliberated, thoughtful decision to act for the enhancement of our own and our society’s well-being with full responsibility for all the implications of that action – then and only then, the human liberation of women will be a reality”.

Christine Gudorf points out that “In our world over half the human beings are victims of the moral callousness of the other half, and many of those victims are now sacrificing another group of victims in their attempts at self-assertion and self-defense”.

Carrying a pregnancy to term is always a choice.

Looking at pregnancy as a form of bodily life support, Jung argues that, with respect to organ donation, “Persons do not have a right to or claim upon parts or the use of another's body, because living bodies are primordially personal.” Carrying that ethical stance to its logical conclusion, she contends, requires us to honor the claim to “bodily integrity made by women in regard to their reproductive capacity.”

One realization I came to as I read each of these novels, one after another, is that in the moment(s) when a woman is deciding whether or not to carry a pregnancy to term, deep-rooted cultural and personal assumptions about motherhood are revealed.

And carrying a pregnancy to term is always a choice. Sara Ruddick, one of the first women to gain prominence as a philosopher, contends that every mother – every single one – is “adoptive” (her quotation marks). She explains that “To adopt is to commit oneself to protecting, nurturing, and training particular children. Even the most passionately loving birthgiver engages in a social, adoptive act when she commits herself to sustain an infant in the world.” While this understanding obscures important realities about adoption as method of family formation (Jean Keller has a great analysis of this in “Rethinking Ruddick’s Birthgiver/Adoptive Mother Distinction), this perspective reinforces Ruddick’s reminder that “In any culture, maternal commitment is far more voluntary than people like to believe.” What Ruddick terms "adoption" follows an earlier, equally significant choice, however: the choice to carry a pregnancy to term. Consider, for a moment, the way that Sarah Palin has talked about her pregnancy with her youngest son: “There, just for a fleeting moment, I thought, I knew - nobody knows me here. Nobody would ever know.”

The moral nuances and the sense of choosing the least worst option are palpable.

In working on that chapter, I realized it contained the heart of my dissertation. For another year and a half (and then three more years as I revised it into my book), I lived with women facing excruciating options and making the best decisions they could for themselves, their potential children, their families and lives. Deirdre, faced with a boyfriend who loved her passport more than he loved her and impacted by her mother’s invalidism in ways that she hadn't come to terms with. Xuela, whose mother had died in childbirth, leaving her unprotected and unmothered in a highly racist community. Martine and Mary, each traumatized by the sexual assault she has endured.

One of the most chilling comment about legal efforts to regulate abortion that I've heard comes from Ellen Goodman. Writing about Susan Struck's pre-Roe legal fight to carry her pregnancy to term, Goodman points out "this reality: a government that can force a woman to have an abortion is the same government that can force a woman to continue the pregnancy." Reproductive justice advocates like Loretta Ross remind us that this same government also implements laws and policies and encourages attitudes that will interfere with -- and even prevent -- many women (especially women of color) from raising their children to adulthood.

It isn’t only fictional women who grapple with the difficult decisions and challenging concerns that pregnancy raises. Some women hold their experiences in privacy. Other women tell their stories for a variety of reasons, and in those so very personal accounts, the moral nuances and the sense of choosing the least worst option are palpable. To circle back around to Ross, reproductive justice demands that we honor the reality that carrying a pregnancy to term is always a choice.

……

Editor’s note: A PDF version of this article is available here for readers interested in specific page numbers from which quotes are taken in this article.